Should a Backward Caste candidate get reservations even if his parents also used them?

What the NRI success teaches us

I was part of a movement against reservations during my MBBS (medical school) days. The government had suddenly introduced an additional 27% reservation for OBCs, and we were worried that open seats would be reduced by 27% to accommodate the reserved candidates. Many of us were not against reservations as a whole. We believed some sort of affirmative action was needed for the weaker sections of society. But we did not want open seats to reduce. We also wanted a rationalization of the reservation system, so that the ‘creamy layer’ of SC/ST/OBCs did not get reservations.

One common suggestion was to limit reservations to one generation in the family. If the parent truly benefited from reservations, the son/daughter should not be needing it any longer. And if the parent had not benefitted, then the son/daughter is also not likely to benefit.

This argument made a lot of sense to me back then. As I matured, I realized that the issue is much more complex. I kept wondering what the true answer would be.

How can we have an evidence-based approach?

Now, I am a doctor. Modern medicine is founded on the pedestal of evidence-based management. If you want to introduce a new drug for controlling blood pressure, you need to first conduct a (randomized controlled) trial. Take a group of patients with high blood pressure. Give the new drug to half the patients, and give the other half a placebo (a bland sugar-coated pill akin to water). If those who got the drug have better BP control than those who got placebo, it means that the drug works, and vice versa. Majority of the public understand this process fairly well thanks to the Covid vaccine trials.

Can we extend such trials beyond medicine? We certainly can. Indeed, Abhijeet Banerjee received his Nobel prize predominantly for his work in conducting such trials in the field of economics. Can we then conduct a trial to prove whether reservations can be stopped after one generation? Theoretically yes. We would need to take a group of SC/STs whose parents have already received reservations in education and jobs. Half of them would continue to receive reservations while the other half would not. We would then need to keep a close eye on them for decades to see whether one group is doing socioeconomically better than the other. If say both have equivalent income, health and life expectancy, then second generation reservations do not work. On the other hand, if the former group does better than the latter, it proves that second generation reservations are still needed.

Conducting such an experiment is a tall exercise, given its duration and various practical and political compulsions. Such a trial is not going to happen. How can we come to an answer then?

We often face a similar situation in medicine as well. In such circumstances, we use real-world data to glean an insight. While not as definitive as a randomized controlled trial, it does help point the needle one way or the other.

For example, imagine two countries who have used two different Covid vaccines to provide universal Covid vaccination. Country A used Covid vaccine A, while country B used Covid vaccine B. Both vaccines were developed against the alpha strain, and now the delta strain has spread. If country A gets ravaged by delta while country B does not, it would be safe to conclude that vaccine B works better against the delta strain (assuming equivalent masking and social distancing behavior).

What the NRI successes teach us

The recent successes of Indians abroad have probably provided such real-world data to answer the question of reservations across generations. Many Indian immigrants of first-generation descendants have recently reached great heights abroad. Sunder Pichai, Satya Nadella, and Paresh Agrawal are the CEOs of amongst the biggest companies in the world, Kamla Harris is the American Vice-President while Vivek Murthy is the Surgeon General of US, and Rishi Sunak was one of the two contenders for UK Prime Ministership. In my own field of medicine, I see many Indian-origin immigrant doctors becoming departmental chairs and section chiefs abroad.

As immigrants and someone of different race and nationality, these individuals would have been socially disadvantaged in their countries. They would have faced discrimination similar to what SC/STs face in India. Their meteoric rise is proof of how ability and performance trumps other considerations in the West.

I am not saying that everything is hunky dory there. But these examples show that in the West, one does not require multiple generations chipping slowly against the social order and making incremental gains to rise up the ladder. By and large, if one works hard and demonstrates capability, the system there allows the person to rise quickly, be it at a corporate, medical, academic, or political level.

The harsh reality

If our ‘one generation’ argument against reservations was true for India as well, many first or second generation SC/STs post the reservation era should be on top corporate boards, C-suite level jobs, high political positions and in the upper echelons of academia in India.

I Googled to check. The facts are sobering. About 25% of our population is SC/ST as per the 2011 census (16.6% SC and 8.6% ST). And yet, only 3.5% of corporate boards are SC/STs (90% are Brahmins or Vaishyas) (2010 data). There are only 11 SC/ST faculty members across 20 IIMs (including none in IIM-A) (2019 data), and 4 SC/STs in the 82 secretaries to the Govt of India (2019 data). I can rattle out many more numbers, but all the evidence glaringly points to the same thing.

A person’s caste is clearly a much bigger weight to carry in India compared to race and ethnicity in the West. Affirmative action including reservations in the education and service sector have not allowed SC/STs to overcome the overt or subconscious bias they face in everyday life. Those whose parents have received reservations still need further affirmative action, as they have not been able to rise enough.

Many would argue that this data actually shows that reservations do not work at all, and hence should be stopped. I disagree. Data from women’s reservations in panchayats shows a visible benefit both in terms of administrative quality and women’s empowerment. However, it also shows that women have had to face many additional obstacles to be able to succeed. There is no reason why the scenario is any different for SC/STs; it is just that they have an even steeper mountain to climb.

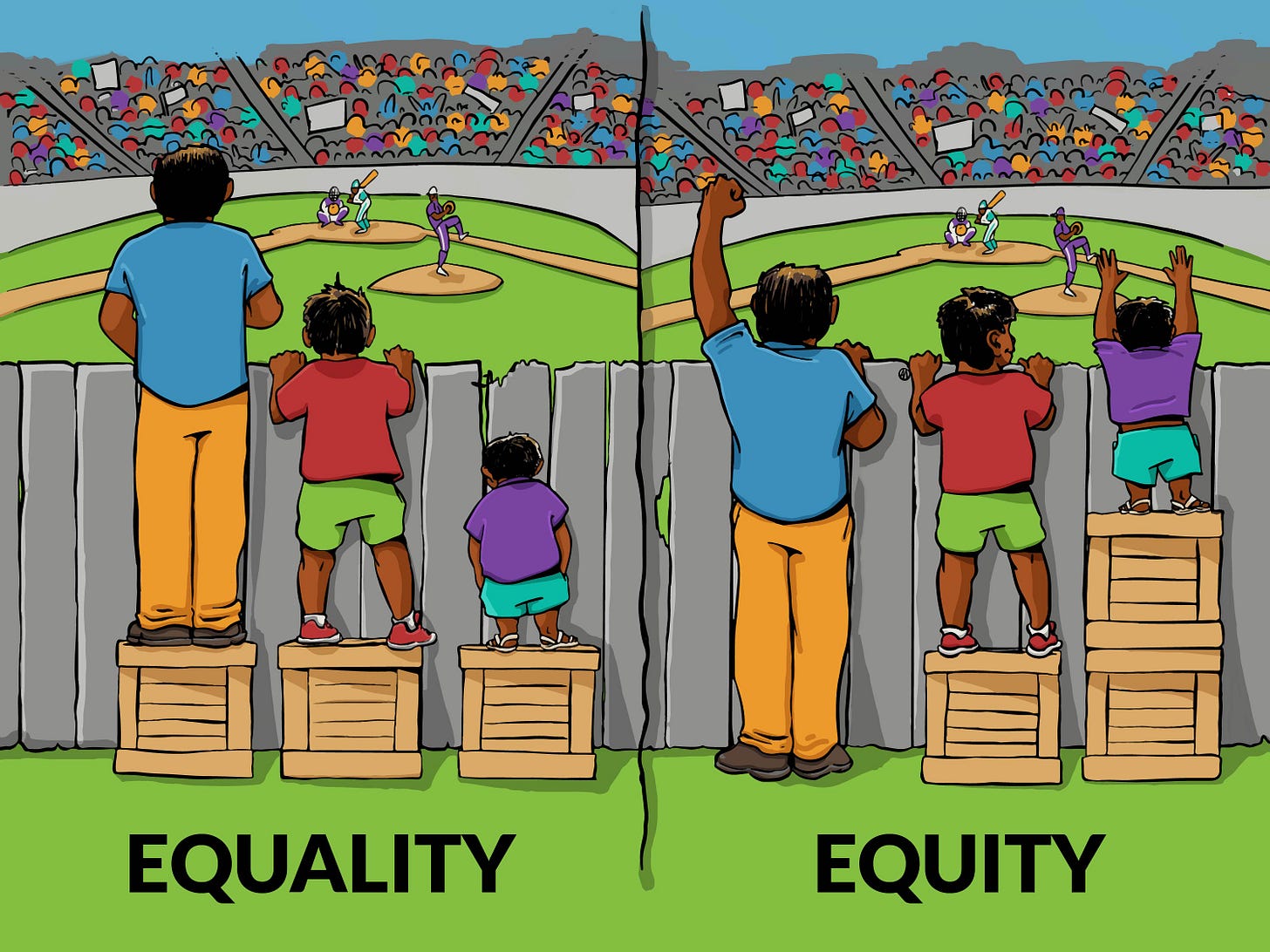

Reservations are probably a small but important part of a much more holistic intervention needed to improve the socioeconomic standards of the SC/STs. We need more concerted efforts to tackle societal prejudices and discrimination, as also targeted interventions to increase the confidence of the SC/STs in tackling social stigma. We of course also have to achieve the delicate balance between reservations and merit, but ensuring equitable (different from equal) opportunity is paramount in our deeply flawed society.

The successes of our NRIs are worth celebrating. But they also hold a mirror to our societal wrongs. We would do good to acknowledge just how much work is still left to be done. India has progressed so much despite 25% of its population barely crawling ahead. Just imagine where we can reach if we allow them to blossom as well to their full potential!

- Please subscribe to this newsletter if you haven’t already. It’s free! Also do share and spread the word!

- You can follow me on Twitter at https://twitter.com/maangomanindia (@MaangoManIndia) and on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/maangomanindia

- You can read this blog on Medium as well at https://medium.com/@mangomanindia/should-a-backward-caste-candidate-get-reservations-even-if-his-parents-also-used-them-659f0848dbc0